The ghouls amongst you will want some gory detail.

Very well. You shall have it.

The ghouls amongst you will want some gory detail.

Very well. You shall have it.

You can trace the route of the Presidential motorcade on the picture above.

It is marked in blue, and the direction of travel is from top to bottom of the picture.

Oswald is waiting in a room

on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository, overlooking Elm Street.

The clock on the Wall of the Book Depository is showing 12.30 local time when

the leading car, carrying The President,

The First Lady, Governor of Texas John Connally and his wife

turns off Main Street into Dealey Plaza.

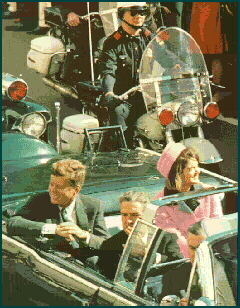

The picture on your left shows them some 30 seconds later,

just before making the turn into Elm Street itself.

Another 30 seconds, and the car is just above the'm' in 'Elm Street', when

Oswald fires three shots in rapid succession. Two strike The President, one in the upper back, one in the head.

The bullet pictured below hits Kennedy

in the back of the head, emerges through the side of his head and continues

on through the back, chest, right wrist and left thigh of

Governor Connally.

The wounded are rushed to hospital, but the surgeons can do nothing to save The President, and

he is pronounced dead exactly 30 minutes later.

At least, that is what happened according to the report of The Warren Commission, the body set up under Earl Warren, Chief Justice of the United States, to investigate the killing. But American citizens always lean to thoughts of conspiracy, and according to a recent survey, fewer than 20% of them believe in the single-lone-nutter account. Indeed, a brief survey of the web will reveal upwards of 3,000,000 sites devoted to various competing conspiracy theories.

Was the mob involved? Did J.Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, arrange the killing? Was there a backup assassination squad in case Oswald failed? How could a single bullet cause four separate wounds? How could anyone fire three shots in 5 seconds? Were there also killers positioned on the grassy knoll? On the roadside above the triple underpass? Who was the man with the umbrella, and why did he vanish? How come all those who gave eye-witness testimony to The Warren Commission were dead within ten years? And so on. And so forth.

But you and I, of course, are above all that. We are, after all, philosophers, people

of high mind and noble ideals....

Everyone working in the area is familiar with the name of Oswald and the competing explanations of the assassination, for - purely by accident - professional interest has converged on just three sentences, given iconic status by logician Ernest Adams. Here they are, in glorious technicolor:

[A] If Oswald didn't shoot Kennedy, then somebody else did.

[B] If Oswald doesn't shoot Kennedy, then somebody else will.

[C] If Oswald hadn't shot Kennedy, then somebody else would have.

I suggest you pause for a while, and work out your own response. Think first of all just of the sentences. Does [B] belong with [A] on purely grammatical grounds? Or is it grammatically more akin to [C]? And then reflect upon the messages which these sentences encode. Their meanings, as we might say. Is [B]'s message parallel to that of [A], or is it closer to the message encoded by [C]?

Give it a good five minutes, and commit yourself to a view before you click on

the answer.

These are large claims. To see them demonstrated, sign up for

And now, back to the main story.

And if not, come along anyway. Correct Revolutionary Thinking

will be explained over the eight weeks.

Click on the flag to return to the main body of the text.

The Dallas Police Department mug-shot of Oswald, taken when he was brought into custody 90 minutes after the shooting.

Click on the image to return to the main story.

President Kennedy three months before the assassination.

Click on the picture to return to the main story.