The stained glass of St Salvator's chapel

The glazing of St Salvator's chapel has undergone many dramatic changes over the centuries. We have no evidence of what the original mediaeval scheme looked like, but given the ornate architectural survivals, it is probable that finely patterned, grisaille glass would have played an essential role in the decoration of the church. The chapel was stripped of its stained glass during the Reformation and nothing more is known about how it was glazed until the 18th century.

During the restoration undertaken between 1759–1760, the windows were cleared of their mullions and tracery and were fitted with wooden frames and shutters. John Oliphant's drawing of the chapel (c.1767) reveals the disagreeable aspect these 'improvements' gave to the building. Nevertheless, the shutters remained in place until the late 1840s when they were taken down and the windows filled with clear glass. Though elegant and attractive in execution, this clear glazing was only a temporary feature of the chapel. The major restoration of the building begun by Principal Forbes in 1861 saw the chapel completely re-glazed.

The 1843 schism within the Church of Scotland saw the departure of the most extreme Calvinists from the ranks of the ministry, leaving the moderates the freedom to embellish their churches. The resulting relaxation of the Kirk's rules banning 'graven images' from church buildings led to major re-glazing programmes throughout Scotland. This was the period of the gothic revival that produced the Houses of Parliament and other fantastically ornate buildings. For St Salvator's, the gothic revival meant the addition of a 'cloister', a few architectural embellishments and stained glass.

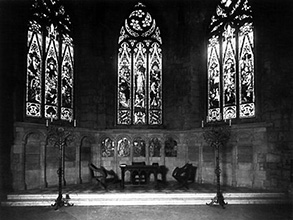

Of the eight stained glass windows Principal Forbes commissioned from Hardman & Co., only two survive in situ. However, photographs provide us with some idea of the overall impact of the scheme. The 1860s restoration saw all of the windows in the chapel fitted with delicate new tracery. However, the westernmost window, and the small window set above the south door were glazed in diamond-leaded, clear glass. In addition, the first window to the east of the door was never executed. In its place is a fine window in pre-Raphaelite style designed by Henry Holiday in the 1880s.

The next phase in the glazing programme followed on from the installation of the organ loft during Principal Irvine's improvements. The insertion of the loft split Hardman's large plate glass window into two. Hence the west end of the chapel has two small upper windows and one small lower one. The lower window would appear to be the first to have been fitted with stained glass. This armorial window is a memorial to Bishop Kennedy, Provost Skene and Edward Harkness.

Harkness died in 1940, and the deterioration of the window would indicate that it was executed around that time, when the leading available to artists was of a poorer, less durable quality. The windows in the organ loft are the work of the same artist, but as they are better preserved than the window in the ante-chapel, they may be of a slightly later date. The artist responsible for these windows was Herbert Hendrie.

Principal Irvine praised Hendrie's designs in a memorandum sent to the chapel buildings committee in September 1948. The letter also reveals the difficulties the University encountered in its dealings with Dr Douglas Strachan, a full description of which may be read in Juliette MacDonald's excellent essay An Unfulfilled Vision: The Commission for St Salvator's chapel. The six watercolours by Strachan, held in the University Collections, provide some idea of the exciting scheme the artist planned for the chapel. However, they were never executed, and instead the University turned to Gordon Webster to produce a new window for the centre of the apse. In response to this, Principal Irvine wrote: "it is generally agreed that the new centre window … is strikingly successful and, in my opinion the two flanking windows should also be entrusted to Mr Webster…"

However, Irvine's recommendation was not followed through and the other four modern windows in the chapel are all the work of master artist William Wilson. Two of these windows are figurative, but the other two are abstract designs that form a complex matrix for the arms of Bishop Kennedy and other important figures from the University's past.

20th-century installation

All of the windows installed in the chapel in the 20th century have been fitted into new mullions, the spindly gothic revivalist tracery being heartily disapproved of by Irvine's architect, Dr Fairlie. The new mullions and tracery are much thicker and return the chapel's facade to something of its original appearance. This can be seen most clearly when the chapel is compared with the near contemporary Church of the Blackfriars in St Andrews.

The history of the glazing of St Salvator's chapel reflects the experience of Scotland's churches as a whole. Despite, or rather because of the controversy over Strachan's designs, the chapel today allows the visitor to trace the evolution of Scottish attitudes towards stained glass from the middle ages to the present.

Gordon Webster (1908–1987), the son of famous stained glass artist Alf Webster, made a major contribution to the decoration of Scotland's churches. Working from his studio in Glasgow, Webster created many fine windows for the Church of Scotland. His work for the chapel consists of the superb crucifixion scene in the centre of the apse.

Gordon Webster (1908–1987), the son of famous stained glass artist Alf Webster, made a major contribution to the decoration of Scotland's churches. Working from his studio in Glasgow, Webster created many fine windows for the Church of Scotland. His work for the chapel consists of the superb crucifixion scene in the centre of the apse. John Hardman (1811–1867) was one of the pioneers of the stained glass revival of the 19th century. His Birmingham based operation started out as an ecclesiastical metal works but, at the suggestion of A.W.N. Pugin, the business expanded into glass manufacture in 1845. Pugin designed for the firm until his death in 1852 when this role passed onto his nephew John Hardman Powell.

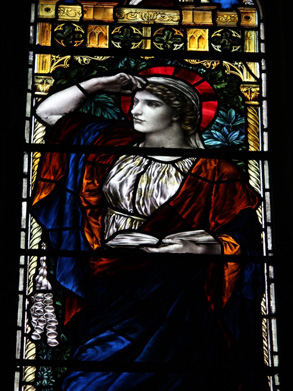

John Hardman (1811–1867) was one of the pioneers of the stained glass revival of the 19th century. His Birmingham based operation started out as an ecclesiastical metal works but, at the suggestion of A.W.N. Pugin, the business expanded into glass manufacture in 1845. Pugin designed for the firm until his death in 1852 when this role passed onto his nephew John Hardman Powell. The artist Henry Holiday (1839–1927) deserves to be better known. Eschewing the sentimentality and archaism of his peers, his stained glass designs are strong and dramatic, and reveal a brilliant understanding of the use of colour. However, his reputation has been overshadowed by that of Burne-Jones, whom he succeeded as designer at the firm of Powell & Sons.

The artist Henry Holiday (1839–1927) deserves to be better known. Eschewing the sentimentality and archaism of his peers, his stained glass designs are strong and dramatic, and reveal a brilliant understanding of the use of colour. However, his reputation has been overshadowed by that of Burne-Jones, whom he succeeded as designer at the firm of Powell & Sons.